A while back I wrote here about my visit to the Future Library in Oslo and I was recently interested to hear that the next author to feature would be Mexican novelist/essayist Valeria Luiselli. In May 2024 Luiselli visited the Nordmarka Forest to hand over her manuscript and walk through the saplings of the Future Library forest. In 2023 she noted how the project brought her a “feeling of total freedom” as “This is a piece that no one I know will read - maybe my baby daughter, because she’s two, and she would be 93 - so it could be. But other than her, I don’t know anyone that would read it. So there’s a freedom in that.”

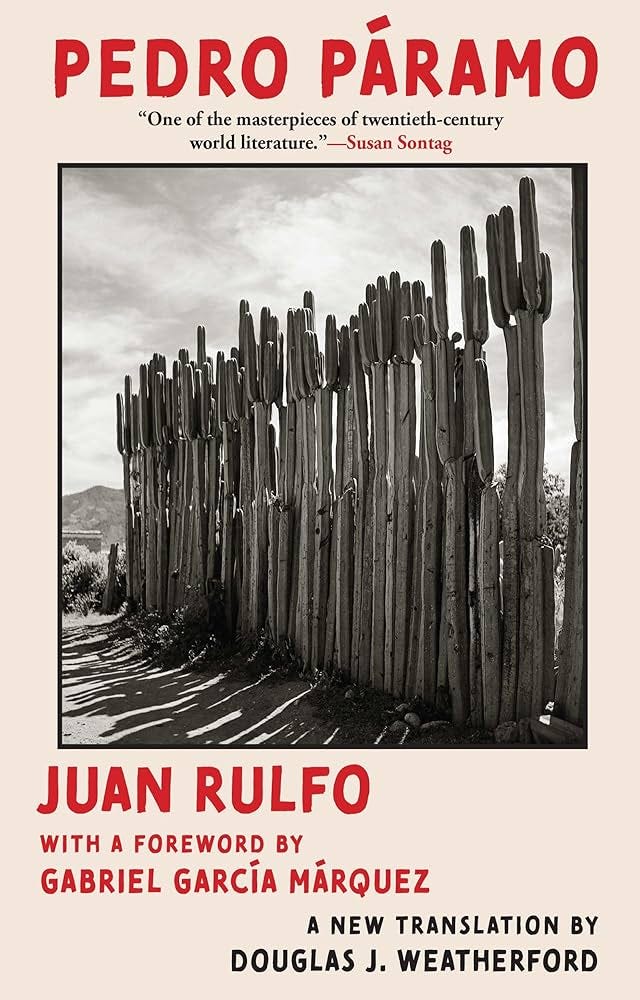

I’ve started a thread of books I’m reading in 2024 on my Bluesky account. I’m not planning on any kind of detailed analysis of what a year of reading will tell me but it may be interesting to look back on it and see if there were any trends (more men than women? More non-fiction than poetry? Etc.). I know that I finished 2023 reading a lot of women (Miriam Toews, Molly Hennigan, Hannah Sullivan) and that I began 2024 reading a lot of Bolaño). I’m tracking this online as previous years’ reading lists were physical and have a habit of going missing. I cannot remember all the reading I did in 2023 but what I do remember is that my book of the year was one originally published in 1955: Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo. This latest version comes to us via a new translation by Douglas Weatherford (who was, in fact, the external examiner for my doctoral viva), an expert on the work of Rulfo in the English language. This latest translation far surpasses all previous attempts at rendering this strange, enigmatic masterpiece in English. But don’t take my word for it. Here is Fernando Sdrigotti writing in the London Magazine and here is Valeria Luiselli for the New York Times.

A few years back I was asked to contribute an entry on Aztec poet-king Nezahualcóyotl for the online Literary Encyclopedia. I was then asked to contribute one on Luiselli. This one never really came together and was not published. I found it a lot easier to write the requested overview about someone long dead than a contemporaneous writer, especially one so mercurial, who seemed to be doing something very different with each project. I was a big fan of Los ingrávidos (in English, Faces in the Crowd), Luiselli’s first novel. It seemed clear to me that Los ingrávidos was partially inspired by Rulfo’s first novel. So I scribbled these notes for the article that never materialized:

Los ingrávidos begins with an epigraph from the Kabbalah:‘¡Ten cuidado! Si juegas al fantasma, / en uno de conviertes’ [Beware! If you play with ghosts, / you become one] and the notion of ghostliness makes its way into the novel at an early stage. The entry point to the realm of the undead seems to be signalled by an unusual encounter the female narrator has at Gilberto Owen’s former residence where she has accidentally locked herself out on the roof and is forced to spend the night. The girl who eventually saves her announces that her name is Dolores Preciado, though her friends call her Do. Later on, in the Gilberto Owen narrative section another character named Dolores Preciado / Do is introduced. She seems, in fact, to represent the bridge between different spatial and temporal realities. Her name is, of course, the same as that of an important character in Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo. It is Juan Preciado’s mother, Dolores, who instigates her son’s journey to Comala, therefore encouraging him to enter the ghost world.

Luiselli has stated that the starting point for the novel came from Owen’s diary entries and his fears that he was disappearing: ‘He would play with the idea that he was disappearing, instead of becoming blind. The idea of ghostliness came from that character. That, plus the rhythm and experience of ghostliness in the subway. That was the initial intuition that I started following.’ She was, however, at first, reluctant to write a ‘ghost story’:

But I never thought to myself: Write a ghost story. Especially because one of my favorite Mexican writers, Juan Rulfo, is the modern ghost story teller. His novel Pedro Páramo, is one of the most brilliant books ever. So it wouldn't at all be in my interest to write my own take of his book. I would never have aspired to do it. What is fascinating about Rulfo though, and I reread him when I was writing the novel to figure out how he had done it, is that in one single time frame, he lets the dead and the living coincide. (Analise Chen, ‘Interview with Valeria Luiselli, author of Faces in the Crowd’, Electric Literature)

By acknowledging Rulfo’s influence within the novel, through the Do character, Luiselli pays homage to Mexico’s most famous ghost story while simultaneously constructing a singular piece of work. A more humorous reference to Rulfo comes at a later stage, when Owen speaks of his plans to write a novel centering on his time in New York and Mexico, a novel in which the characters are all dead but they don’t know they are dead. When Salvador Novo tells him that a certain young Mexican writer is working on something similar, he is furious. In this way Luiselli comments upon the difficulties associated with a Mexican writer composing a novel that shares any similarities with the work of Rulfo. The inclusion of ghosts or characters who fear they may be becoming ghosts also provides Luiselli with a mechanism for including real-life characters within a fictional setting. The narrator does not only follow in the footsteps of her admired writers from the past, she enters their space, enters them. They do likewise.

At one point in Los ingrávidos the narrator, perhaps responding to her husband’s requests for clarification, attempts to name the things that are real, as opposed to fiction: ‘Existe una casa, el crujido de la duela antigua, los estremecimientos internos de las cosas que poseemos, las ventanas palimpsésticas que guardan huellas de manos y de labios.’ [A house exists, the creaking of the boards, the internal shivering of the things we possess, the palimpsestic windows that hold the impressions of hands and lips]. Not only does the palimpsest provide the perfect metaphor for the passing of time as glimpsed in the present, it also represents the way in which fiction and non-fiction blend into each other. An author begins a novel about a relatively obscure poet and subsequently enters his world, as he does hers. As Los ingravidos progresses, the identity of the narrator becomes more and more elusive, as does the relationship between fact and fiction. On a regular basis the female writer character’s husband reads the fragments of text that she is in the process of writing. At one point, after reading an excerpt, he asks: ‘¿Es él que dice eso o eres tú?’ [Is it him saying that or you?]. This occurs shortly after the narrator, on the subway, sees her own face superimposed upon the face of Owen:

Pero no era mi rostro; era mi rostro superpuesto al de él—como si su reflejo se hubiera quedado plasmado en el vidrio y ahora, yo me reflejara dentro de ese doble atrapado en la ventana de mi vagón.

[But it wasn’t my face; it was my face superimposed upon his—as if his reflection had become imprinted upon the glass and now I was reflected inside that double trapped on the carriage window.]

In this way the real and the imagined fold in upon themselves and bleed into each other. Los ingrávidos asks ontological questions throughout. The past can only be appreciated in the present. The past and present overlap: ‘Una novela horizontal, contada verticalmente.’ [A horizontal novel, told vertically]

In other news, my walk from Co. Roscommon to Dublin City has now finished. In just four days I ended up walking around 180km. Thanks to the generosity of family, friends and followers I gathered 176% of my donation target. Donations (for Medical Aid for Palestinians) are still open and if anyone is interested you can find out more here.

As always, the best way to support me and my work is by buying my book. Let the Dead is available here. Or you can subscribe, like and share this post for free!