TARAHUMARA

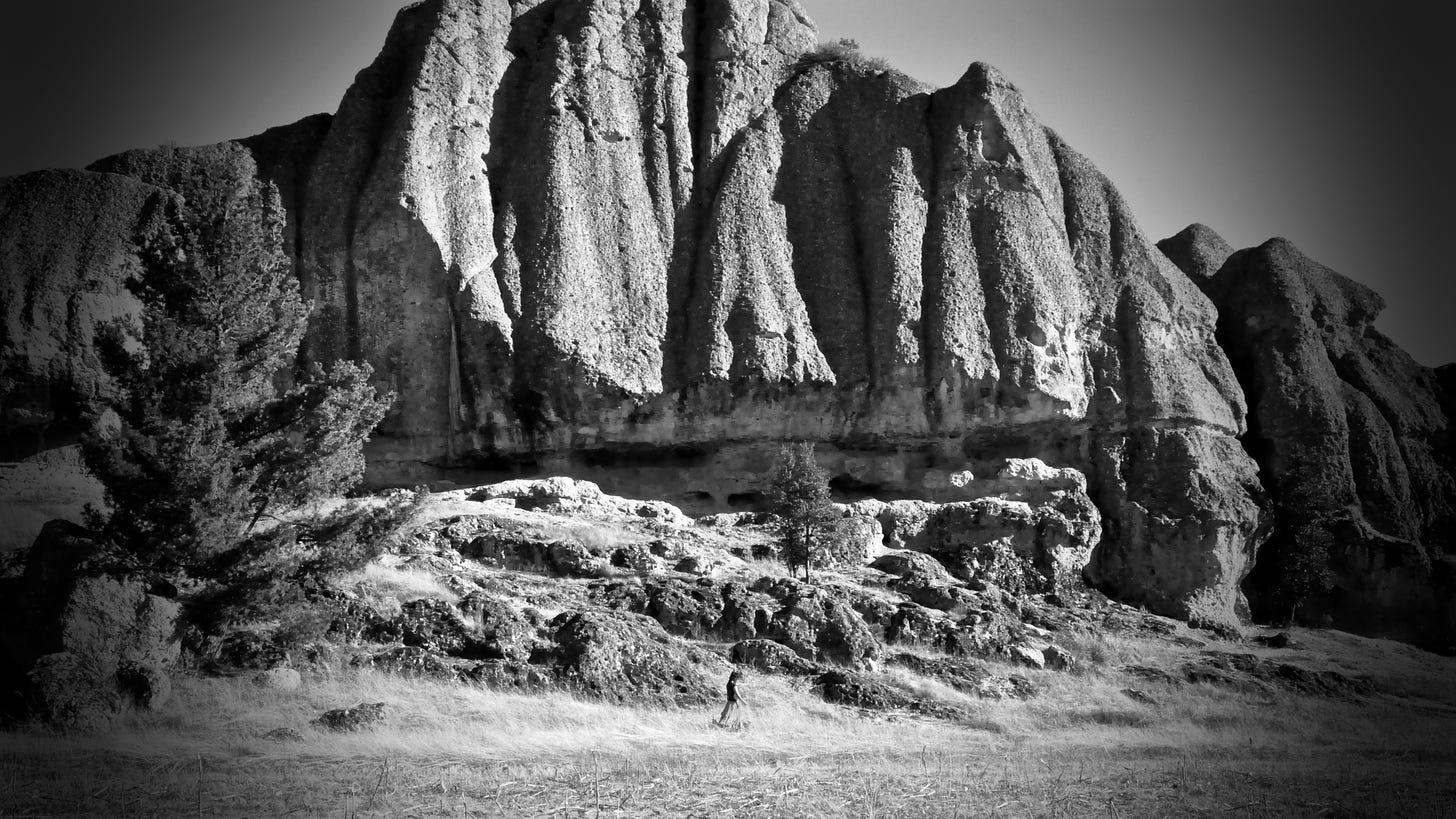

Arriving dusty in a cold sweat, swirls of dry earth inhaled. The winter sun beginning its descent. The valley of mushrooms, the valley of frogs: the boulders of Tarahumara country, capriciously sculpted by constant wind, look like things, look like faces.

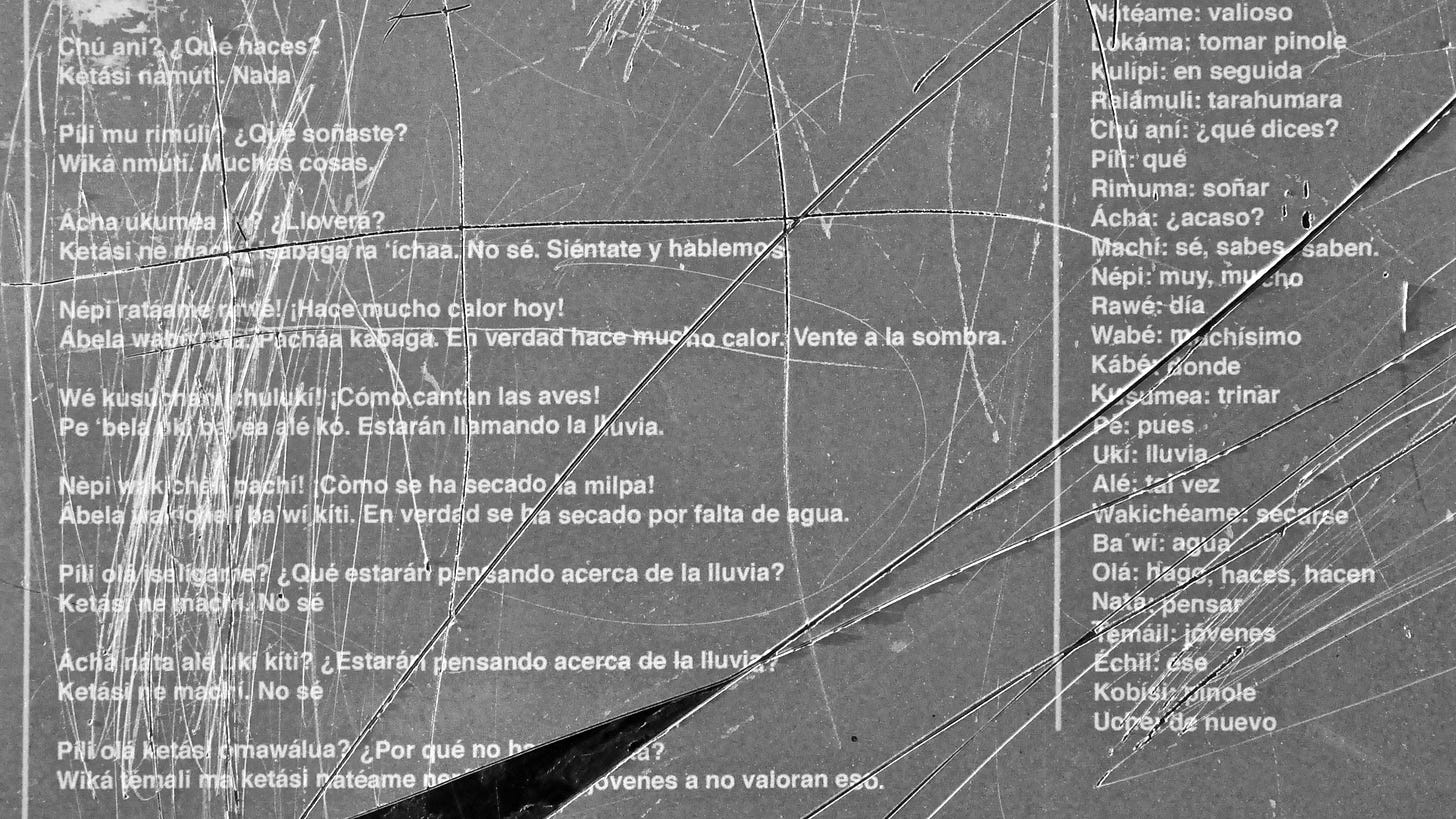

We made it to San Ignacio de Arareko having walked out from Creel after breakfast. Grey bricks and a stone cross, the squat geometry of the church. Children playing asked to be photographed. The authorities had provided informational wooden boards for walkers and cyclists. Images, maps and useful phrases in the Rarámuri tongue. Photographs of locals outside the church. Their faces, and some of the phrases, had been scratched out.

*

The first time I saw Creel was on a computer screen. A single lens camera documented the arrival of armed men just after dawn. They moved in formation, as if they were police. One of them seemed to be in charge and the others lined up at his truck window to receive clumped portions of cocaine. They needed to be wakeful. They were looking for something, looking for someone. Each heavily armed, they stopped cars, searched citizens. The camera (controlled by someone, someone who watched the whole scene) followed them, zooming in to areas of interest. They made their way down to a large white rectangular building with many windows and split up, attempting to enter from various angles. The camera captured the steam of their breath, moved to the right for a moment to the digital gold of the sunrise flooding a dry field. Then back to that building. Eight people killed, including a fourteen-year-old girl. Bullets from a distance usually sound harmless. Dry bangs like firecrackers. Flashes from their weapons. They lit the place up.

*

Píli olá ketási omawálua? ¿Por qué no h——————?

Wiká temali ma ketási natéame pe——— ——————jóvenes a no valoran eso.

Nearly all of the phrases had been vigorously scratched at but these two, in particular, seemed to have provoked the most violent reaction, the plastic surface having been dug into and partially removed. I may not have transcribed them correctly. They are difficult to make out. The first phrase in English would be something like: ‘Why have/has ….. not …….?’ The second phrase: ‘......the young people to not appreciate that’. Maybe the phrases enable a visitor to ask why the Tarahumara have not fostered traditional values in their young people. But no, that wouldn’t make much sense. I asked an old man to explain and he said he didn’t want to.

Earlier in the day we visited a cave in which two families live. Clay trinkets for sale and the morning smoke of something recently cooked. I spoke to one of the residents. She was young and told me that it had snowed already twice that season and that the winter time is tough. Her name was Esther. She told me that an older woman who wouldn’t speak to us was named María. Esther was patient and answered my questions. She told me that twenty-six people lived in the cave and they received regular visitors. We bought a tiny clay cup and spoon. Esther was selling some cloth tortilla warmers with a word written on them: ‘Kuira’. I asked her what it meant and she said, in English, ‘hello’. Maybe the younger generation have realised there is now no way around it, they have to put up with the interlopers and our stupid questions. We left and I shook her hand and said ‘Kuira’. She laughed and spoke to some of the other ladies and then they laughed too. What I should have said was ‘Ariosibá’, which I think means goodbye.

Edited excerpt from a text originally published in Winter Papers 4 (out of print). Photographs by Liliana Pérez-Brennan.

I have written a book of poems. Let the Dead will be published by Banshee Press in June of this year. If I have any news, I will share it here: details on launches, readings, festivals etc. I am not sure what else I will use this space for but if you’d like to find out, please subscribe. If someone is mad enough to become a paid subscriber I’ll send you something, like a handwritten poem.