GUADALUPE

It’s that time of year. Here is a text I wrote a few years back, from another lifetime it seems. Originally published in gorse issue 6. Currently sold out. Images are linocuts by Jonathan Brennan. More of his work is available here. Please subscribe for free and share.

Let the Dead available from Banshee Press here. Order by the 15th for Xmas delivery!

Twin islets, bedrocks of silt and water, but not founded solely upon a lake. Mexico City and, before it, Tenochtitlan, both constructed upon hallucinatory apparitions and the meanings attached to them. An eagle resting upon a prickly pear cactus with a snake in its mouth. A sign. A sign to build a city of causeways and narrow canals. An easy image for the Spaniards—the snake, the eagle—the battle of good and evil, a symbol to be misused for the teaching of morality. Quetzalcoatl—the feathered snake, the plumed serpent, from the Toltecs to the Maya, more likely this image represented a sacred location for the Mexica, those wandering mercenaries. To cease their meandering. To build an empire. No proof of this event will ever exist but the image has been institutionalized and forms the basis of the nation’s coat of arms. The Templo Mayor on the corner of the Zócalo, considered by some to have been built in the place of the vision. Some prickly pear cacti still grow among the ruins. Not much of the temple was left by the Spaniards. The greatest ruins in Mexico are located in places the invaders neglected. Ruins that were already ruins when the conquistadors arrived, swallowed by muscular foliage. Places of wonder like Chichen Itzá and Calakmul. Large, monumental and, crucially, functioning temples were razed with immediate fervour. But nothing can be reduced to nothing—the stones re-used to construct in civilized squares, to build the cathedral and the palacios. Tezontle, a hard yet porous stone that retains heat, caramelizes the Zócalo each twilight—baked earth hues that warm the pulsing heart of the country. The evening walkers, the children with balloons, the conchera dancers, the brujos performing limpias, the ruddy tourists and the pregnant girls, everywhere, young pregnant women; all delicately lit by the reflected light of lambent tezontle.

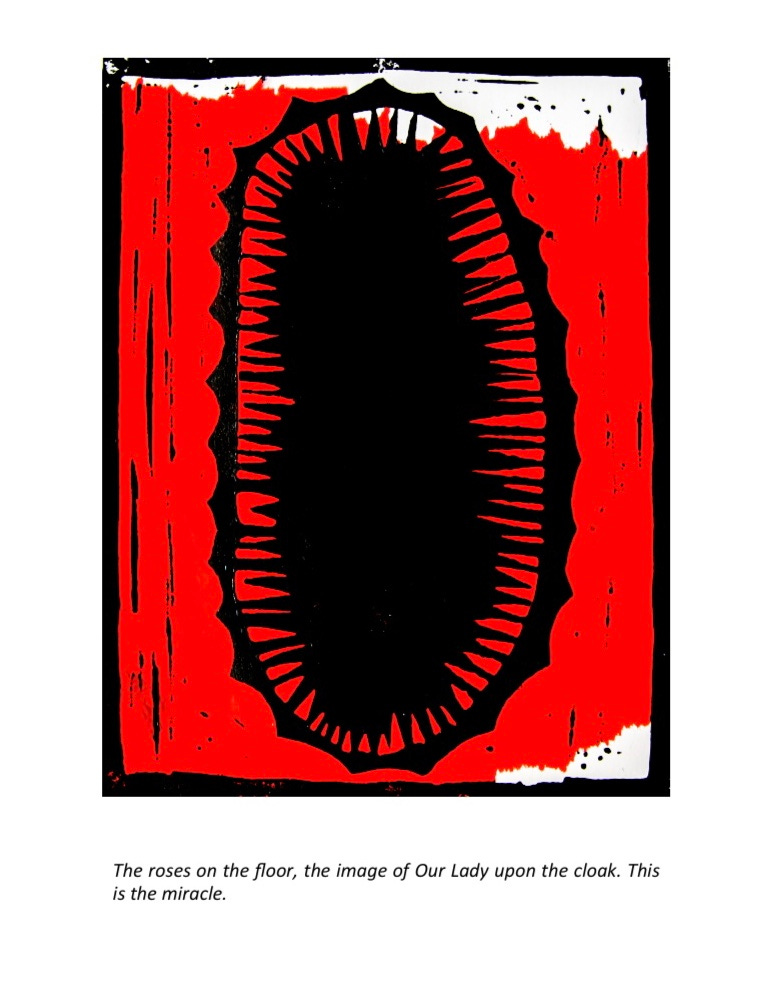

A man walks to the hill of Tepeyac to the north of the city. An indigenous man with a Spanish name, a Christian name. Juan Diego. Tepeyac, a holy hill, former site of a temple dedicated to the mother goddess. He meets a woman. A woman who speaks to him in his native tongue. A dark-skinned woman. She requests that a church be constructed on the site in her honour. Juan Diego knows that this woman must be Tonantzin, the goddess, the mother, the mother of god, the mother of Jesus, madrecita, la virgencita morenita. He tells the bishops of his discovery. They instruct him to go back to get proof. He visits the hill again and finds roses of Castilla, not native to the country, growing in December, upon the summit of Tepeyac. The woman appears to him again and instructs him to gather the roses in his cloak and to bring them to the bishop. Bishop Fray Juan de Zumárraga receives Juan Diego who opens his cloak before him to scatter the roses at his feet. The roses on the floor, the image of Our Lady upon the cloak. This is the miracle. Juan Diego canonized in 2002. When the cloak was sent to a laboratory in the U.S., scientists blew up the face of the virgen and, when they magnified the eyes, the reflection of Juan Diego could be seen. Upon his knees, a bundle of roses in his arms, his mouth agape. With a straight face this was told to me in 2005. Told to me by a believer. Zumárraga, protector of the Indians, prolific writer with an interest in witches (he believed they were merely sick, afflicted by hallucinations, the bad kind). An unstoppable cult springs up around an event in which his role was pivotal. It happened on his watch. No reference to any of this can be found in his extant writings.

That day was so bloody one could not walk the square for the bodies strewn about. Tlatelolco. Once a neighbouring city, a close rival eventually annexed. Witness to three blood baths and an important mirage. Not a far walk from the Zócalo, I reached it with ease and stopped for a look. Merchants of gold, silver, fine stones, slaves, garments, cotton, peanuts, sweet and roasted roots, the skins of otters and jaguars, beans, chia, chickens, rabbits, hares, ducklings and canoes with men selling little ceramic pots of human shit for the purpose of tanning leather. Immortalized by a Diego Rivera mural and Bernal Díaz del Castillo's words, the square was once a massive marketplace. Now, La plaza de las tres culturas. The three cultures—Aztec, Spanish and, ultimately, Mexican. Bernal Díaz tells how myriad Spaniards swore they saw St. James the Moor Killer riding his horse above the chaos, striking down Aztec warriors with ease. The battle won—the final battle. The fall of Tenochtitlan. Santiago Matamoros was a regular at such events, helping the Spaniards defeat the heathen invaders of the homeland and, years later, inflicting his carnage upon the Mexica, those New World Moors. And He saw the Conquest and the Conquest was good. In 1968 governmental forces massacred hundreds of student protestors in the same spot. Who? Who were they? The next day, they were nobody. Rosario Castellanos, her words upon a stone, rupturing the government's silence, imposed and unsustainable. 1985, that massive earthquake. Large swathes of the megalopolis reduced to inhaled rubble. The flat grey slabs underfoot, the ruins of the Mexica city, the church made from the toppled temples and the rectangular despair of the apartment blocks. Brutalist architecture built upon butchery. Grey brick upon brick. A shiver tumbled down the backbone—a residual energy or the weight of prior knowledge? Transubstantiation? Synergy—something more than the sum of its parts. Skeletal hand in skeletal hand / lie the lovers of Tlatelolco. The plaque beside them explains who they were. This pair died during one of the battles. One male, one female, discovered fleshless, their finger-bones touching. A glass roof for gawkers to oooh at their love. The sun sat low on the rectangles. I made my way back to Reforma, which quickly bifurcated. I took the right fork, now called Calzada Guadalupe—Guadalupe's Avenue. Pilgrims picking up the pace. The Basilica felt near.

Vaginal apparition, Queen of Mexico, Empress of the Americas, secondary patroness of the Philippines, La morenita, virgencita, madrecita, Tonantzin. The village of Santa María Tonantzintla can be reached on foot from Cholula. Tonantzin, 'Our Holy Mother' and tla, 'the place of', therefore, 'The Place of Holy Mary, Our Sacred Mother'. The parish church a voluptuous exercise in techni-coloured syncretism. Designed and decorated by local artisans, the interior a riot of colour in which Catholic and indigenous symbols almost wrestle for prominence. Structural vestiges of the Pre-Hispanic past seen now and we forget these grey stone cavities were once covered in an orgy of fruit tones. Tonantzintla church represents, perhaps, despite the presence of Catholic iconography, our best depiction of how the interior of a Mexica palace or temple would have looked. Catholic saints beside Eagle Warriors and Xochipillis abound. Everything has a double interpretation. Semi-divine anthropomorphs, humans with wings, nothing new here. The Eagle Warriors with their yellow plumage could just as well be called angels. The conversion of a savage to Christianity is the conversion of Christianity to savagery. The butchery of the conquistadors and their banners of blood sacrifice—the leap of faith must have been easy. Catholic saints and the mad eyes of cleft-lipped papaya-vomiting heads juxtaposed against pagan images of suns and moons. A pluri-cultural societal mosaic. The essence of the virgencita's attraction and longevity. Her bi-racial derivation. A mahogany-faced speaker of Nahuatl, come to mother the new race in the wake of the destruction of their old gods. Thesis of Octavio Paz, flogged to death—it still holds some water. To hold the orphans in her arms. A Catholic re-birth—ending to begin, just like a universe.

Very straight and very wide. Cortés and his army marched along the Calzada Iztapalapa, and into Tenochtitlan. Now called Calzada Tlalpan. No longer a causeway through a lake, but a hellish, clogged thoroughfare better travelled on the light rail transit system, el tren ligero. Constant heavy traffic at high altitude. Walking this road is hard on the lungs, hard on the eyes and hard on the ears. Now it's famous for cheap hotels and prostitutes, many of them trans. They stand outside the hotels during the hours of light and darkness. They must do business, they’re always there. The long causeway is difficult to cross, not so many bridges as one approaches the heart of the city. Underground passages are more common. In the underpasses venders flog Tupperware, cheap jewellery, sandwiches, second hand mobile phones, pornography and other things more advisably purchased elsewhere. Closer to the Zócalo the ads for the brujos pop up on either side of the road. Passing CENART, the National Centre for the Arts, banners everywhere—the Ayotzinapa 43, the normalistas, trainee teachers murdered by state sponsored criminals in the state of Guerrero. But we all know it was more than 43 and they weren't all students and one of them was left without his ears, without his eyes and without his face and the coroner told the police who told a reporter that that was done while he was still alive. Up to Taxqueña, maybe half way, still walking alone. A massive junction, the joining point of the tren ligero and the metro system as well as a bus station. The pathway finishes and the only option to walk the side of the motorway below the junction. The road turns narrow and I look for other options and end up lost, well not lost but back to the same spot. And then I see them, other pilgrims, real pilgrims with pictures hanging from ropes around their necks, pictures of the virgencita. Girls, women and one man. They look to the man, as confused as I am about how to proceed. He points straight ahead, as I feared, the only option to walk the lower roadway and hug the side for fear of being run over. I follow them. They smile and, as usual, say nothing, assuming I don't understand Spanish. I smile back. I clench every muscle as if that will protect me from the lorries that trundle past, almost brushing my beard. Not long after re-surfacing, I see more pilgrims. They must have gotten off a bus at Taxqueña. Just a short walk down the road, we get our reward. For pilgrims free tacos and mandarins.

Reaching the corner of Pino Suárez and República de El Salvador comes after walking over four hours and I sit down for a rest. About three blocks from the Zócalo. Behind my back a large stone plaque in a state of disrepair commemorates the beginning of the nation, the clash of civilizations. November 8, 1519, on what is now a typical street corner, the meeting happened. Squirrel cuckoo, pink flamingo and quetzal feathers. According to legend the headdress was gifted to Cortés by the Mexica emperor on their first meeting. Some believe it's not a headdress, others that it didn't belong to Moctezuma. What we do know is that it resides in the Ethnology Museum of Vienna. I feel a twang of pain in my ear and send up some fingers to suss it out and it feels like a pimple and I don't know yet I have a blood clot in my ear that will swell to the size and colour of half a plum in the next two weeks. I don't know yet that anesthetics don't work very well in the ear (something to do with the blood flow or, rather, the lack thereof) and that the health centre in Cholula, though free, is not the best place to get this sorted and they'll hold me down and talk about how much I squirm and I'll hear every squelch and bubble of the blood in my ear and the doctor's hot fingers and the lukewarm fluids that burst out over my face and cool immediately like new piss but without the relief. I don't know yet that they'll make it worse and I'll spend New Year's Day in shivering agony in Tamaulipas shaking in my seat as the specialist winces at and apologizes for the pain he causes me. A rupture, a broken dam pop of cartilage liquefying and the impeccable white pain of a thousand SAD lamps and it now looks like a version of wax—melted and re-set by clumsy hands, a child's art-class interpretation of an ear.

Recently diagnosed with spina bifida and scoliosis, months of chronic back pain, the original plan of walking 130 km through the mountains, past the volcanoes, into the megalopolis and on to the Basilica de la Virgen de Guadalupe—it had to be abandoned. The decision instead to walk in to the Basilica along the Calzada de Tlalpan from the ruins of the ancient city of Cuicuilco. From the centre of Mexico City, the metrobus out to the periphery to begin my artificial pilgrimage, needing to get out of town to come back in. Insurgentes—the longest avenue in the city and the second longest in the world and the metrobus route follows the avenue to its termination, a 14km ride from where I get on, a fraction of its full length. One moment, a glimpse of the virgen from the metrobus window, no, not her but Cantinflas—the Mexican Charlie Chaplin, hero of Tom Waits, giving alms to the poor. The centrepiece of Diego Rivera's mosaic at the Teatro Insurgentes. Looking back, I now see that I lifted a lot of my act from Cantinflas. He's depicted by Rivera in front of a church. My friend, the architect Víctor Jiménez, had told me not long before how his daughter once called him to ask what church was represented in Rivera's mural at the Teatro, a question on a phone-in radio show. The answer—the Basilica. Two stars, one either side of his head, Cantinflas replaces Our Lady, a typically irreverent move from Rivera. The metrobus had already passed the Jardín Juan Rulfo, a depressing little traffic island park with a sculpture of Rulfo's head emerging from a book; continuing on to El Parque Hundido, meeting place of Ulises Lima and Octavio Paz as told by Bolaño; UNAM, the autonomous university; and eventually arrives at Perisur, the southern periphery's motorway. That's where I get off, though the city doesn't stop there.

Sit there on the windowsill and don't move. Or watch the football game through the window, that's the World Cup Final you know. I was six and remember well closing the door when nobody had a key, excited to see my uncle and running out to greet him and then they had to break some of the glass to get their hands in to unlock the door. El Estadio Azteca—I had the whole outfit, the sky-blue and white stripes and the black shorts and Maradona across the back and I remember though he didn't score in that game he put Burruchaga one-on-one with the keeper after a perfectly weighted through-ball and 3-2 and that was it. The first time I saw a game at the Aztec Stadium I was 29 years old and wanted to know which goal was the Hand of God goal and nobody really seemed sure. From Cuicuilco down Perisur I had turned off a side road to find a shortcut to Calzada Tlalpan. I got lost and ended up at the Parque de las Novias, the park of the girlfriends, a place that I'd heard of. A small garden known as a hangout for young lovers and I saw teenage girls texting and giggling as their friend's mother messed with her hair. A quinceañera, a fifteen year old princess out now in society and posing with classmate handmaidens—their dresses scrunching in a mist of sweet perfume and I loved them all and they waved and I waved back and turned the corner and saw the stadium looming before me.

Yes, the Basilica felt near, the main crowd had been walking up Reforma. A pathway opened up in the middle of the road and pilgrims thronged around. One man walked on his knees along panels of cardboard, torn from supermarket boxes and his companion lifted up the cardboard behind him and placed it in front of him and I thought with my back I'd rather be the praying kneel-walker than the constantly crouching and bending companion. Free samples of pain medication from the chain pharmacies and plenty of free water and tacos for pilgrims and a general sense of camaraderie and goodwill blanketed all as the sun was sneaking behind the buildings. A carnival of devotion awaited the pilgrims at the gates of the complex. Nuns from El Salvador, quiet men with unutterable sins, their heads bowed in shame, young priests with acoustic guitars, almost naked dancers with feathers praying to Tonantzin, anti-Catholic ranters, a woman handing out free boiled-eggs, a scar-faced old soldier smoking a cigarette, a wall of electric idols, incense burning, copal smoke rising, the old religion is the new religion is the only religion, the only existing today. I drink a paper-cupful of holy water handed to me by a monk. A young girl's mother tells her to go up to me and to give me some of the sweets in her basket. The girl is shy and doesn't want to but I approach and bend down and ask if I can have one and she nods yes and her mother and her mother's friends giggle at my accent and I sit down and look up to the sky. There are no stars. Back to the tezontle of the older churches. Lowering my eyes to the things of this world. Through a haze of smoke and passing-by costumes I see the old Basilica, the new Basilica and various other chapels, some of them cracked by tremors and time and slanting columns tilting on the sediments. All this will fall. All this. I remember why I'm here, to see the image, the first image, the real image. The queue is short. The dancers paid their respects the night before. Midnight prayers to the virgen bring the most rewards. A priest splashes scapulars with holy water and I get some on my face. The cloak is hung highly behind a few rows of gliding-by conveyor belts. I look at it without hope, without expectation. It is a thing of beauty and nothing more. An exquisite image. And it is so much more. Someone told me the crown was removed and her moon platform added. Her skin is not white and she prays for us all, prays to her son, prays to the moon, always wanting only one thing—to save us from pain. Facsimile copies, authorized and official, are available for purchase. The shop is swamped and hectic and teetering on the verge of outright violence and I escape outside to the men dressed as jaguars dancing in the vast esplanade. From the state of Guerrero, one of the poorest, one of the bloodiest. Twin towers of crisscrossed tree trunks with a strong rope in between and the young men take turns to climb and hop along the thick tightrope, performing acrobatics for Our Lady, she could not but approve. Their wives and girlfriends dance below them and the more experienced lads give enthusiastic support to the youngsters and not one of them falls. They all shade their eyes from the now horizontal sunlight. Mass is due soon as visitors start to arrive. Not the pilgrims that have spent the night here and all of the feast day but lighter skinned mass-goers seeming to disapprove of the abject delight of the poverty on display. They arrive in their finery. Their high-heels sound like their money. Sound like their arrogance. Before I go I have to do something. One for my mother back home, photo on the phone and I forget to ever show her. God I'm lighting candles again, still / The sentimental atheist, family / Names a kind of prayer or poem, my muse / Our Lady of Guadalupe.

Walking to a hotel in the darkness the candles light the way, the candles and the mobile phones, stream weightlessly down the avenue. Some more free fluids, some more free food, some more free friendship. Real friendship, the excitement of the football game, the quivering perfumed long coats of the funerals in Mount Jerome, the sadness of the fathers at their daughters' wedding, the screams in a darkened cinema, the mass witnessing of a miracle, the speaking in tongues at the Pentecostal church on the outskirts of Corpus Christi, the simultaneous orgasm in the back of a van—there is nothing simpler and nothing as perfect as the shared emotion. Not far from the gates the kneel-walking man crawls and he now has two companions laying down his cardboard carpet in front of him. Sweat drips in heavy globules from original carpet-layer's nose and his face is solid, his suffering controlled. The crawling man doesn't sweat and keeps mumbling his prayers. People pat him on the shoulders, pray for him, walk alongside him for a while, kneel beside him and whisper encouragement into his ears. I walk on by, I'm eager for bed.

Cuicuilco, with its circular pyramid, possibly the only one in the world, location of the first major civilization to reside in the Mexican Valley—finally reached, symbolic starting point of my walk. In its heyday located on land at the southern shore of the lake. Covered now in hardened lava, almost certainly destroyed by Xitle, a now extinct volcano, and then abandoned. The bearded elders endured the decimation / of their tribe without uttering a syllable. I entered freely and walked the straight entrance up to the circular platform. I sat down and read for a bit. Walcott's Omeros. The sea, the salt, the sun, the shoals of mackerel, more Odyssey than Iliad. 360 degrees, I made a video on my phone. The roller-coasters of Six Flags in the haze to the west, the buildings encroaching on all sides, Cuicuilco on an island of green on the edge of a vast concrete breastplate. To the north, Perisur and unending rivers of automobiles. Silence on the platform. That Mexico City silence, not an absence of sound (something unimaginable) but, rather, a buzz, a dull vibration. It's always there. It comforts you when you sleep. It's the faraway sounds of the cars, the trucks, the lorries, the taxis, the footsteps, the tapping pencils, the coughing babies, the cinemas, the rubbish collectors, the factories, the stadiums, the schools, the striking unions, the politicians, the groans of the homeless, the screams of the beggars, the chuckles of lovers, the metro, the buses, the protestors marching, the complaints of the few, the prayers of the many. It's always there, always going on, that Mexico City silence—all that I could hear. Time to start walking and turn my eyes from the sun. When he left the beach the sea was still going on.